The Man Who Canceled L.A.'s First Movie Museum

|

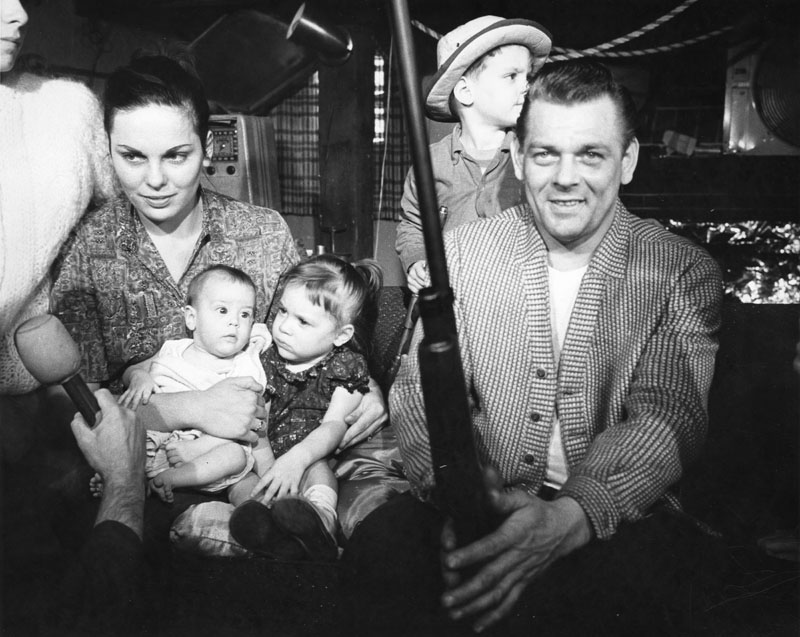

| Steven E. Anthony. Photo by George Brich |

We're told it took a century of dreaming for Los Angeles to realize the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Left on history's cutting-room floor is the fact that L.A. came this close to having a ginormous movie museum in the 1960s. It was stopped by one aggrieved citizen with a gun, Steven E. Anthony. Anthony's tale falls somewhere between Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and MAGA America. It involves treacherous Young Republicans, Hollywood elites, and a flurry of flimsy legal arguments taken all the way to the Supreme Court. The story ends not with a museum but with a parking lot, paved from the paradise of one arguable sociopath.

Like LACMA, which was in the planning stages simultaneously, the Los Angeles County-Hollywood Museum was to have been designed by William A. Pereira. Supporters included a galaxy of Hollywood royalty from Gloria Swanson and Raymon Novarro to Gregory Peck and Ronald Reagan. The museum was to span TV as well as film, and eventually the music and radio industries were thrown into the mix.

As Pereira put it, visitors "would step into a world of illusion." They would buy tickets from audio-animatrons of Clark Gable or Marlene Dietrich. Among the attractions would be a massive stage set recreating ancient Rome and showcasing the tricks of perspective, lighting, and stagecraft used in blockbuster costume dramas. There would be a shrine to the Oscars and another for the Emmys. Two working sound stages would permit visitors to view real Hollywood productions. The complex's signature feature would be a looming tower (rather than a sphere) for offices and collection storage.

The estimated cost of $6.5 million was modest, even in 1960s dollars. In comparison, the original LACMA ran about $11.5 million. Fresh off the success of Disneyland, Walt Disney assured the museum's board that the project would be "an obligation for the millions of tourists who come to Hollywood."

The museum was to occupy a high-profile site next to the Hollywood Bowl. The County donated the land—except for 6655 Alta Loma Terrace. That was a small, privately owned parcel holding the English Tudor home of Steven Anthony, a 33-year-old Barney's Beanery bartender, his wife Elona, and their three young children. The Anthonys owned only a half-interest in the property, but they refused to sell. (The holder of the other half-interest had sold.) The Anthony family was served eviction notices, and on Feb. 8, 1964, Sheriff Dept. deputies attempted to remove them. Anthony, "cradling a shotgun in one hand and a baby in another," refused to leave.

|

| Elona and Steven Anthony, with children and shotgun. Photo by George Brich |

The deputies backed down, giving the family a few more weeks to move out. Anthony spent the reprieve giving blustering interviews to the media. "I'm not leaving," he told the L.A. Times. "If Sheriff Pitchess tries to evict me like he did three weeks ago… I'll be waiting inside with my shotgun. Only this time I will have my buddies at my side." He warned that his friends were fellow ex-marines. "The minute anyone tried breaking in, they will be in for one hell of a surprise."

Anthony and his attorney argued that eminent domain could not apply to a public-private partnership like the LAC-Hollywood Museum. (LACMA, and many American museums, involve a similar partnership.) Anthony took his case to the California Supreme Court and then the U.S. Supreme Court. Both batted away the complaints as having no merit.

Anthony had told the press he would abide by the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling. Instead he reversed himself. "I'm perfectly willing to die for this," he said. "A man has to die for something he believes in." He said he bought 300 rounds of ammo.

If that was a bluff, it worked on County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn. He suggested appeasement: "Let's remember we're just building a motion picture museum."

The standoff ended on Academy Awards night of 1964 (the one where Sidney Poitier won Best Actor). Anthony was watching on his black-and-white TV when there was a knock at the door. The visitors were two Barney's Beanery customers who Anthony had also seen at a Young Republican meeting that had honored his struggle against medium-sized government. Anthony welcomed the visitors in.

It was a trap. One of the men stood in front of Anthony's rocking chair, blocking his view of the TV and brandishing handcuffs. Anthony couldn't reach his gun, and the man punched him in the jaw. Outside about 30 deputies had gathered and moved in on the house. Anthony was taken to jail. Wasting no time, the County removed the family's belongings, and bulldozers began demolishing the house.

Anthony was sentenced to 6 months in jail. The house was razed, but the museum was never built. There are at least two explanations for that.

One is that Anthony had become such a folk hero that the museum's backers feared they would be seen as villains. Good optics the baby and shotgun weren't.

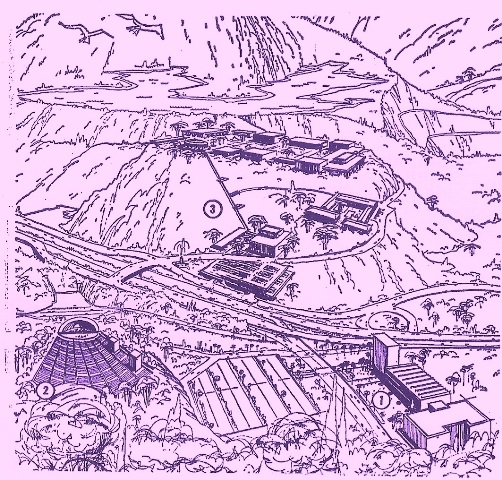

|

| In this conceptual site plan, (1) is the LAC-Hollywood Museum, (2) is the Hollywood Bowl, and (3) is CalArts |

The more overarching explanation is money. The budget kept expanding, as it always does for museum projects. The program kept expanding too. It came to include additional media, and also CalArts. Walt Disney conceived the California Institute of the Arts as a training ground for Disney animators, among other creative types. He wanted it close enough to the Burbank studios to allow easy travel. The evolving plans envisioned a Cahuenga Pass cultural district of the Hollywood Museum, Hollywood Bowl, and CalArts. But linking the museum to another visionary, underfunded project didn't reassure funders.

A committee headed by Barton Lytton concluded the funds for the Hollywood Museum just weren't there. Lytton was a McCarthy-era snitch turned savings-and-loan tycoon who helped establish LACMA. On his advice, the Hollywood Museum's supporters threw in the towel a year after the showdown with Anthony. (Lytton himself later defaulted on his pledge to LACMA, causing the art museum to pry his name off his Pereira-designed wing.)

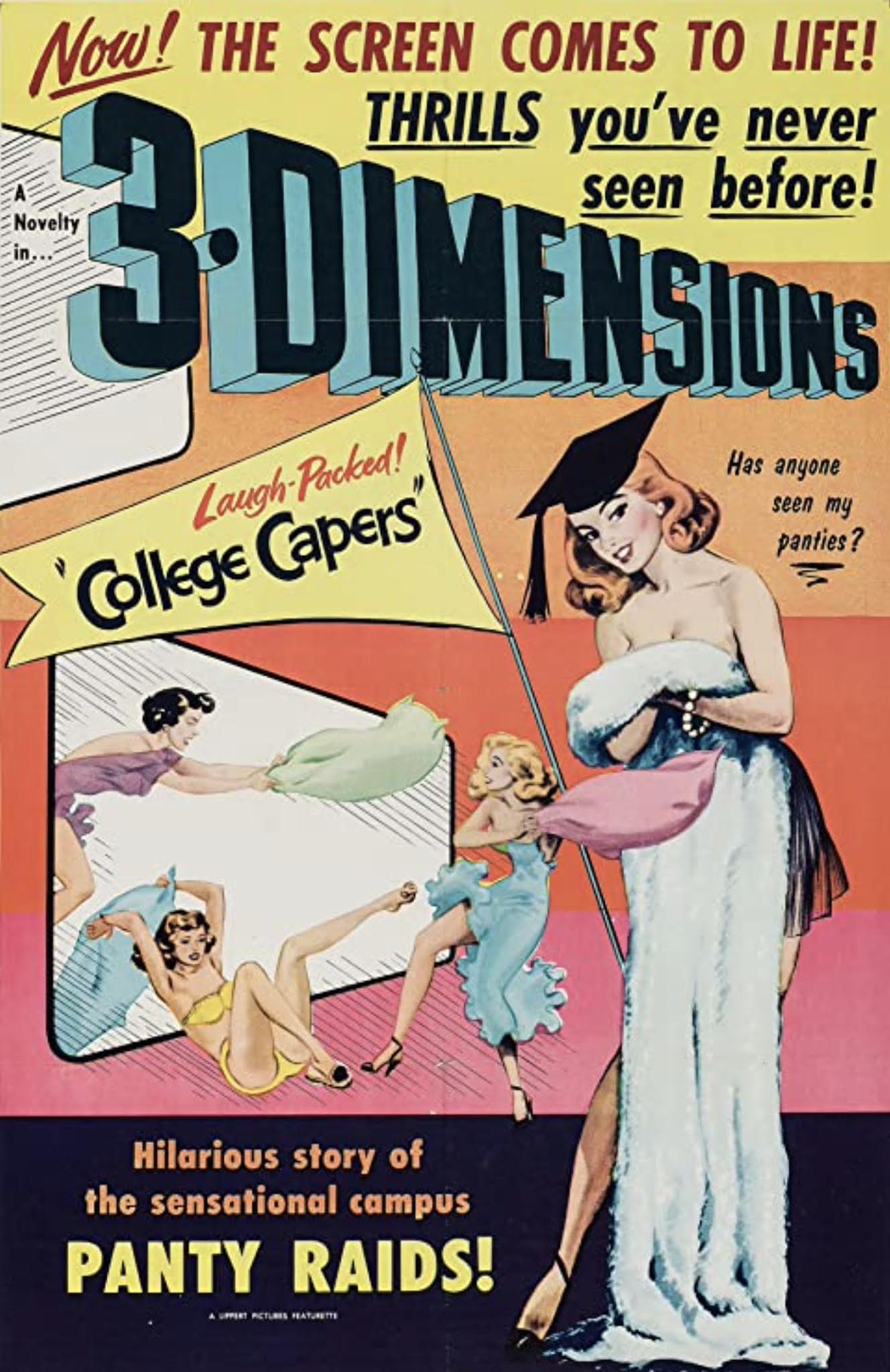

In 1976 L.A. Times reporter Jack Jones did a follow-up piece. Anthony and his family were then living in a mobile home in the upstate town of Sonora. He was still bitter about the eviction, "just like in a communist country." He spoke of suing L.A. County for the loss of "priceless formulas for a three-dimensional movie process" left him by the home's former owner, cinematographer Gordon Pollock. Known for working on Charlie Chaplin's City Lights, Pollock also participated in the less canonical 3D short College Capers (1953).

6655 Alta Loma Terrace is now a spillover parking lot for the Hollywood Bowl. The larger parcel acquired for the movie museum did in fact get one. In 1985 the Lasky-DeMille Barn, Hollywood's first film studio, was moved to the site, becoming today's Hollywood Heritage Museum.

|

| Hollywood Heritage Museum. Photo by Barry Finnegan |

(Reporting and quotes are mostly from vintage Los Angeles Times stories. For more details on the Anthony standoff, see online articles by Steve Vaught and Andrew B. Hurvitz, to which this post is indebted.)

Comments

As for "sociopath," that's altogether in the eyes of the beholder, and what political narrative he or sse favors or doesn't favor.

Personally, I'd say that Micheal Govan and his band of merry dilettantes fit the word "sociopath" as well as any.